The “English nationalist” bogey quickly becomes a reason to marginalise the English, rather than listen to and engage with them. By John Denham

The idea that “English nationalism” caused Brexit is now embedded deeply in the national conversation, but it’s had too little serious discussion. Commentators and academics alike slip easily into the nationalist explanation, whether they’re writing from a sympathetic or hostile viewpoint. It’s a lazy analysis that now threatens attempts to argue a pro-EU case.

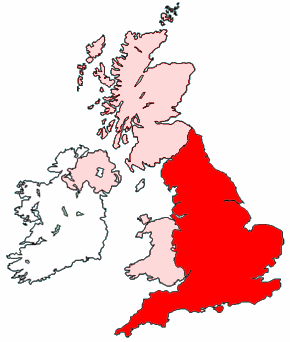

At the weekend, Observer writer and academic Will Hutton called for a “popular front” to resist “English nationalism”. For leading pro-EU campaigners, it seems that the English must be made into the enemy. Such lazy anti-English prejudice helped fuel Brexit in the first place: Remain campaigned as Scotland Stronger in Europe, Wales Stronger in Europe but, in England only, as Britain Stronger in Europe. The English were not worth talking to. Now anti-Englishness is a risk to any effective campaign either to remain in the EU or to achieve a soft and collaborative Brexit. It may be telling that there’s no mention of England or the English on the People’s Vote website.

As we know from both Scotland and Wales, it is a mistake to equate a strong national identity with political nationalism. Both have movements and parties that reflect their national identity and claim to advance their nation’s interests, but only some of that politics is expressed as nationalism. England, on the other hand, lacks almost all every expression of a political nationalism. It has no mainstream nationalist party and no public intellectuals who would call themselves nationalists.

The cultural expression of Englishness is patchy and inconsistent and is not linked to a national politics. Demands for political recognition, through English Votes on English Laws or an English parliament, have more support than is often appreciated but are hardly urgent, vibrant, popular demands. While unionist parties in Scotland and Wales see it as essential to talk to national identity, mainstream parties in England are marked by how rarely they speak the nation’s name. There are small fringe groups: but they are just that. English people have a strong sense of national identity, but this does not mean they are driven by nationalism.

Understood like this, the English vote for Brexit was more a cry from the disenfranchised (hence “take back control”) than English nationalism writ large. Yet, despite the evident weakness of any genuine English nationalism, the “English nationalist” bogey has a powerful propaganda value. It quickly becomes a reason to marginalise the English, rather than listen to and engage with them. If all Englishness can simply be written off as nationalism, then the fears, experiences and aspirations that go with it can be ignored. Yet, if the English do feel that things have gone against them for a long time, surely the priority should be a politics that listens, responds and offers a better future?

The leaders of the Brexit campaign understood the world view of the English so much better than the Remainers. While none were English nationalists, nor did they use English symbolism, they did claim to offer representation to people who felt ignored. Calling for a popular front to defeat the English will merely fuel the worst fears of those who voted Leave. As the former Labour MP Graham Allen tweeted this week: “Elitist Remainers got us into this mess and – in learning nothing – seem determined to keep us there.”

Professor John Denham is Director of the Centre for English Identity and Politics at the University of Winchester, and a former Labour Cabinet Minister.